Shipboard life in the 16th century

Pablo E. Pérez-Mallaína

Professor, University of Seville

Those who believe the old saying ‘things were better in the past’ to be true normally forget the hardships of the daily lives of our ancestors. Thus, in the fantastic world of the galleons and fleets that linked Seville with the Indies, not everything was filled with the dazzling brilliance of the treasures they transported. The ships of His Catholic Majesty also bore witness to the everyday existence of their crews, men who customarily paid with the effort of very hard work for the enormous benefit the kings and powerful of their time gained by receiving the rivers of silver that flowed from the other shore of the ocean.

The conditions of habitation aboard the ships of the Carrera de Indias (Indies Route) can be described, without reservation of any kind, as horrific. Overcrowding reached extreme levels, such that the average space per person was no more than one and a half square metres. So that you may clearly understand the meaning of that number, consider that it is equivalent to 100 people living together in a 150-square-metre house for many months, not to mention the non-reasoning animals that were also on board! With reference to the latter, some, such as the hens and the pigs, were taken to provide food during the crossing, and others were simply parasites of every type and species..

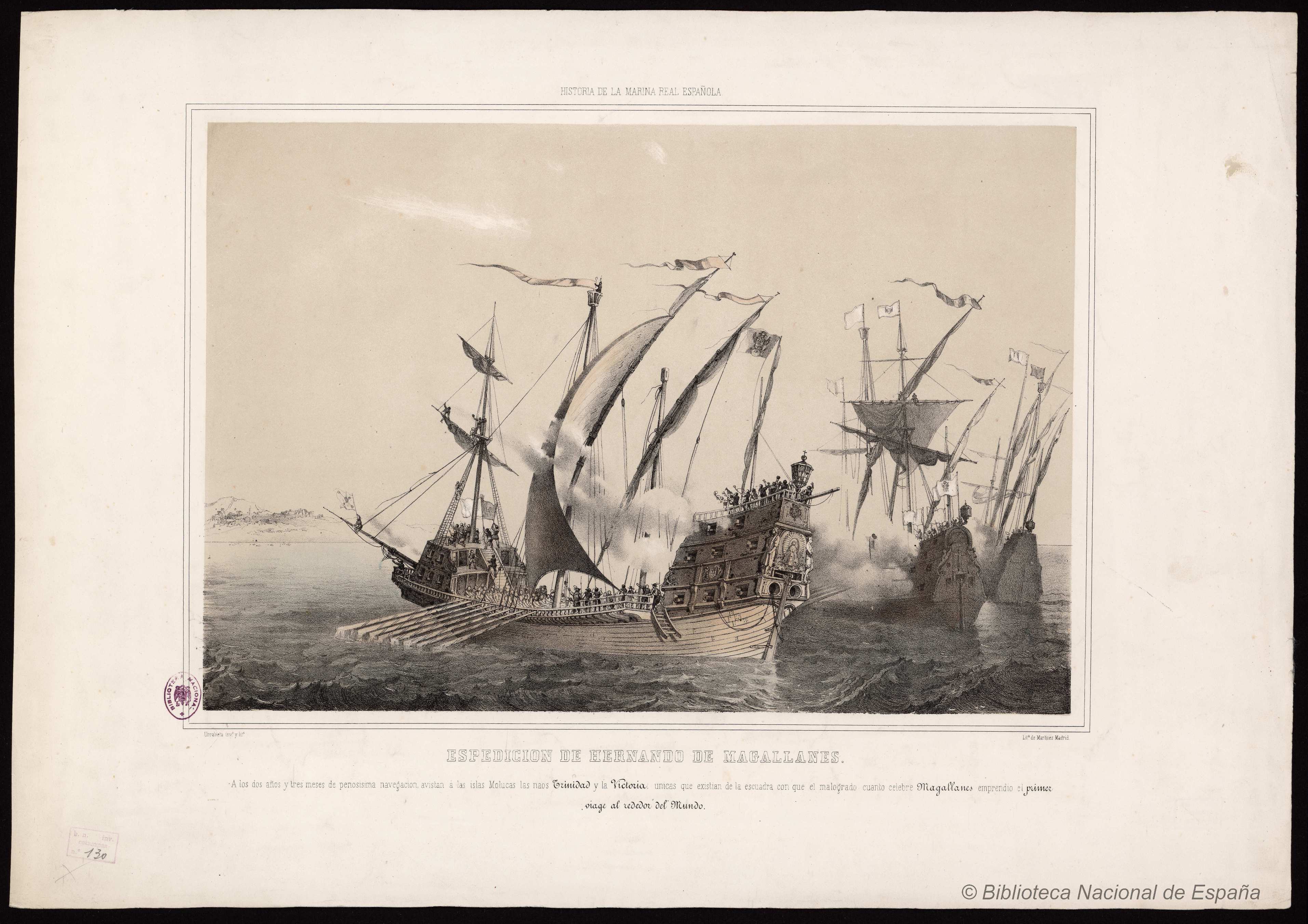

Crew, soldiers, passengers, everyone had to occupy very small spaces, with passage being ridiculously expensive. The more well-off hired a modicum of privacy by means of boards and curtains, with which they constructed provisional cabins. Thus, the between-decks, where open areas should have been left in order to operate the guns, were filled with cubicles

formed by screens and provisional walls. When an enemy was spotted, it was necessary to dismantle this temporary architecture and clear the decks. This is the origin of the Spanish

expression for ‘battle stations’: zafarrancho de combate, which effectively indicates the need to zafar, that is, clear and remove obstacles from, the ranchos, or spaces where the crew

stayed.

If to the overcrowding we add the heat of the tropical sailings and the filth, which was a product as much of the customs of the time as the lack of fresh water with which to bathe, we

have a complete picture which we would not hesitate to describe as terrible. One joker even stated that His Majesty’s ships could be smelt before they were seen, a good way to

summarise this topic.

The onboard diet presented a basic paradox. The only safe way to preserve foods was to keep them salted or dehydrated, and to the misfortune of all the travellers and crew, fresh water was always a scarce resource, which from the beginning was harshly rationed. Water jars took up a lot of space and this had a negative impact on the ship’s profitability. Therefore, masters and stewards always tried to carry tight rations to the cuartillo, which was the most common unit of capacity at the time. Thus, while the rations were made up of salt fish, jerked beef or double-baked biscuits (the famous hardtack), drinkable liquids were always scarce. Thirst was then one of the greatest torments to which travellers and crew were subjected.

Of course, on the voyages, there were also moments to enjoy some of life’s pleasures. The crossing turned particularly peaceful when, after passing the Canary Islands, the fleets allowed themselves to be carried by the trade winds. The sea was usually calm, and with the wind in their favour, they spent many days hardly needing to change the number of sails hanging from the yards. Then there was time for the great hobbies of seafarers: number one being gambling. Although this activity was theoretically prohibited, on the ships of His Catholic Majesty, it was common to literally lose even one’s shirt. Dice and cards were the most common tools, although some gentlemen passengers preferred the aristocratic chess. Drinking and chatting were two very customary diversions. However, when there had been too much wine and the comments turned to private lives, there could even be serious altercations.

Reading was also practised on ships, although this was normally a group activity, where one person read and many listened. Seafarers had very high illiteracy rates, over 80%, but there was always the alternative of asking a passenger the favour of sharing one of their readings with the crew. From information obtained by the Mexican Inquisition, we know that the most popular books were – of course! – religious. Despite this, it should be noted that the list of the ten works most commonly read on board also included chivalric novels and even pastoral novels..

Games of love were totally prohibited. On the Spanish routes, crew members were not allowed to bring their wives, meaning that any sexual relations had to be secret. These constituted, in addition to a sin against religion, a crime against authority. On this matter, the instructions given to the generals and admirals of the fleets included, together with obligations of a military nature, those of safeguarding the morality of the persons under their command. Naturally, female passengers were the main sexual target of crew members, and scandals in this respect were not unusual. However, it must be acknowledged that as regarded heterosexual relations, everyone, from the generals themselves down to the last sailor, was willing to pretend and not give the laws guarding morals their full restrictive scope. Much more severe action was taken when a homosexual relationship was discovered, with the implacable morality of the age usually exacting a vicious punishment.